Table of Contents

Ulster-Scots in the United Kingdom

Language designations:

- In the language itself: Ulstèr-Scotch or Ullans

- ISO 639-3 standard: This language has no ISO 639-3 code. It is included within the Scots language as a dialect with the following code: sco

Language vitality according to:

| UNESCO | Ethnologue | Endangered Languages | Glottolog |

|---|---|---|---|

|  | n/a | n.a. |

Linguistic aspects:

- Script: Latin

Language standardisation

The Hamely Tongue: A Personal Record of Ulster-Scots in County Antrim by James Fenton, first published in 1994 and with a fourth edition published in 2014, can be used as a dictionary, with more than 3000 word entries.

In 2013, the Ulster-Scots Academy Implementation Group (USAIG) published the Ulster-Scots Language Guides: Spelling and Pronunciation Guide, in which the authors state that the publication “demonstrates that agreement on standard spellings for modern Ulster-Scots can be, and indeed has been, achieved.” 1)

Moreover, the Ulster-Scots Academy is working on The Complete Ulster-Scots Dictionary: A full historical record of the written and spoken language. It is a work in progress, but part of it, the Ulster-Scots Dictionary Volume 1: English / Ulster-Scots, is available online.

Demographics

Language Area

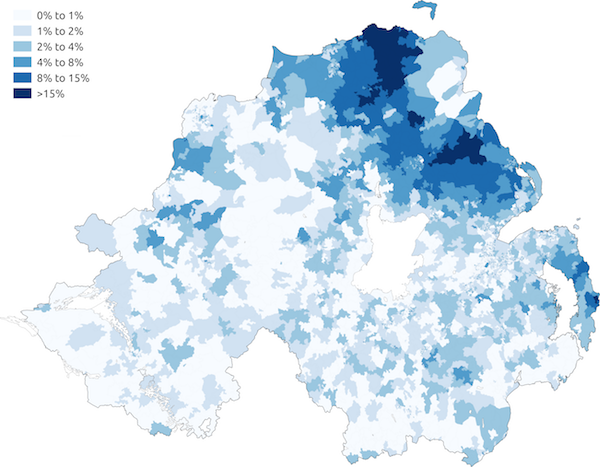

Ulster-Scots is spoken in large parts of Ulster, in the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland, especially within the rural parts of the counties of Antrim, Derry/Londonderry, and Down in Northern Ireland, as well as Donegal in the Republic of Ireland 2).

Left: Map of the isle of Ireland showing the area of Ulster.3)

Right: Map of Northern Ireland showing the percentages of the population who stated that they can speak Ulster-Scots in the 2011 census 4).

Speaker numbers

Northern Ireland

The Northern Ireland Census 2021 registered that, out of the 1,836,619 residents aged 3 and over, 61,032 people (3.32%) can speak Ulster Scots, of which 30,499 people speak Ulster Scots daily (that is, 1.66% of the total population and 49,97% of the Ulster Scots speakers). The highest percentages of Ulster Scots speakers can be found in the local government districts of Mid and East Antrim (7.45%) and Causeway Coast and Glens (7.46%) 5).

The Continuous Household Survey 2019/20 found that 16% of the adult population in Northern Ireland had some knowledge of Ulster-Scots, that is, they can understand, speak, read or write Ulster-Scots. This is an increase compared to the results of the Continuous Household Survey in 2015/16 and 2017/18 . Of the adult population in Northern Ireland, 5% can speak, 4% can read, and 1% can write Ulster-Scots. The survey shows that 34% of the adults who can speak Ulster-Scots, use Ulster-Scots at home at least very occasionally, and 34% of the speakers use Ulster-Scots socially 6).

percentage of adult population in Northern Ireland concerning Ulster-Scots language skills, according to the Continuous Household Survey 2019/20 7).

| can understand | can speak | can read | can write |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15% | 5% | 4% | 1% |

Within the UK: England, Scotland and Wales

According to the UK Census 2021, there were 13 speakers of Ulster-Scots spread across England (12 speakers) and Wales (1 speaker) 8). No data is available for Scotland, as the 2011 census reports on Scots, but not Ulster Scots 9).

Outside of the UK

Ulster Scots is spoken in the Republic of Ireland, in the county of Donegal 10)11), but the Irish census does not include data on Ulster-Scots speakers 12).

No data is available, but Ulster-Scots language communities are (or historically were) present in the USA, Canada, and Australia due to emigration 13)14).

Education of the language

History of language education

Ulster-Scots has been, until recent times, a stigmatised variety, and children were discouraged to use it at school, including punishment for using the language15)16). It is in the Belfast Agreement of 1998 that a need to support linguistic diversity was first articulated: “All participants recognise the importance of respect, understanding and tolerance in relation to linguistic diversity, including in Northern Ireland, the Irish language, Ulster-Scots and the languages of the various ethnic communities, all of which are part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland.” The process of devolvement through the successive agreements and acts that ended up with the establishment of the Northern Ireland Assembly have enabled Northern Ireland to take, among many other things, autonomous decisions regarding education and language policy.

In 2001, the UK government ratified the European Charter for Regional and Minority languages, and recognised Ulster-Scots under Part II. This has provided Ulster-Scots with a certain degree of protection. The singing of the St. Andrews agreement of 2006 (also known as the Northern Ireland Act of 2006), further confirmed this trend towards an expansion in the recognition and promotion of the language. In the agreement it is stated that “The Government firmly believes in the need to enhance and develop the Ulster Scots language, heritage and culture and will support the incoming Executive in taking this forward”. In the same year, a website for schools was launched to help children learn the language17)

Legislation of language education

European legislation

Ulster-Scots is recognised by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages(ECRML. This came into effect in 2001, and the language is protected by Part II, which includes articles on education:

- 1.f: the provision of appropriate forms and means for the teaching and study of regional or minority languages at all appropriate stages

- 1.g: the provision of facilities enabling non-speakers of a regional or minority language living in the area where it is used to learn it if they so desire;

- 1.h: the promotion of study and research on regional or minority languages at universities or equivalent institutions

As Ulster-Scots is not recognised under Part III of the Charter, there are no specific undertakings ratified concerning education. The latest state reports, reports of the Committee of Experts (COMEX) and Committee of Ministers' Recommendations can be found here.

The Inter-departmental Charter Implementation Group (ICIG), hosted by the Department for Communities (DfC), supports the government of Northern Ireland in the implementation of the ECRML.

National and regional legislation

Belfast Agreement of 1998

It is in the Belfast Agreement of 1998 that a need to support linguistic diversity was first articulated: “All participants recognise the importance of respect, understanding and tolerance in relation to linguistic diversity, including in Northern Ireland, the Irish language, Ulster-Scots and the languages of the various ethnic communities, all of which are part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland.” The process of devolvement through the successive agreements and acts that ended up with the establishment of the Northern Ireland Assembly have enabled Northern Ireland to take, among many other things, autonomous decisions regarding education and language policy.

St. Andrews agreement of 2006

The singing of the St. Andrews agreement of 2006 (also known as the Northern Ireland Act of 2006), further confirmed this trend towards an expansion in the recognition and promotion of the language. In the agreement it is stated that “The Government firmly believes in the need to enhance and develop the Ulster Scots language, heritage and culture and will support the incoming Executive in taking this forward”. Since the St. Andrews agreement 2006, language legislation was devolved from London to the Northern Ireland Asembly 18).

policies

Ulster-Scots language, heritage and culture strategy for 2015 to 2035

In line with the commitments of the Belfast Agreement of 1998 and the St. Andrews agreement of 2006, the strategy to enhance and develop the Ulster-Scots language, heritage and culture 2015 to 2035 was developed. Concerning education, the strategy states:

- Aim 1: Promote and safeguard the status of, and respect for, the Ulster-Scots language, heritage and culture.

- Objective 1: To increase respect for the Ulster-Scots language, heritage and culture.

- Objective 3: To develop Ulster Scots as a living language in line with the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

- Objective 4: To meet the Ulster-Scots language, heritage and cultural duties of the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

- Objective 5: To provide sustainable and quality educational provision relating to all aspects of the Ulster-Scots language, heritage and culture.

- Aim 2: Build up the sustainability,capacity and infrastructure of the Ulster-Scots community

- Objective 7: To establish an Ulster-Scots Academy

- Objective 8: To maximise the economic andsocial benefits of the Ulster-Scots language,heritage and culture.

- Aim 3: Foster an inclusive, wider understanding of the Ulster-Scots language, heritage and culture in a way that will contribute towards building a strong and shared community

- Objective 9: To commission quality research in Ulster-Scots language, heritage and culture.

- Objective 10: To increase the amount and quality of Ulster-Scots media provision,particularly television broadcasting and online material.

- Objective 11: To increase positive cross-community attitudes towards, and a wider understanding of, the Ulster-Scots language,heritage and culture

- Strategic outcomes:

- the establishment of a quality,thriving, sustainable Ulster-Scots Academy;

- increased visibility of and accessibility to quality Ulster-Scots provision in the education system;

- an agreed standard written form of Ulster Scots;

- quality Ulster-Scots language, heritage and culture research findings which are disseminated widely and impact positively on the future of Ulster Scots.

However, the further development of the strategy has been delayed, as the Northern Ireland Executive collapesed in January 2017 and was absent until January 2020, due to disagreement on legislation for the Irish language 19)20). The Comittee of Experts of the ECRML recommended the authorities to “adopt a strategy to promote Ulster Scots in education and other areas of public life” in their fifth report (2021)21).

Department of Education language policy

The Department of Education has a language policy that allows the use of Ulster-Scots for communication with the department, but the policy “does not cover language provision within the school curriculum.” 22)

Support structure

The school system in Northern Ireland is in hands of the Department of Education, which in turn is accountable to the Assembly, through the Minister of Education23). Furthermore, individual schools are run by a Board of Governors 24). The Department of Education takes care of education in Northern Ireland, and is responsible for the execution of education policy, mainly in pre-school, primary, post-primary and special education and the youth service 25)

The Department of Education is supported by non-departamental public bodies, called Arms Length Bodies 26). One of these is the Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta, the representative body for Irish-medium Education in Northern-Ireland. This body was established in 2000 by the Department of Education, and receives a grant from the Department of Education to run the organisation and the implementation of an annual plan 27). There is no equivalent of such a body for Ulster Scots, nor is there any of the Arms Length Bodies dedicated to the language.

Currently, the Department of Education has no supporting role for Ulster-Scots in education, and support comes from two other organisations, namely, the Ulster- Scots Agency and the CCEA 28)

Institutional support

The Ulster-Scots Agency

The Ulster-Scots Agency was established as a result of the Belfast agreement in 1998, together with Foras na Gaeilge which has the aim to develop Irish language education. These two boards form the Board of the North/ South Language Body /Tha Boord o Leid in Ullans..

The Ulster-Scots Agency aims to:

- promote the study, conservation, development and use of Ulster-Scots as a living language;

- encourage and develop the full range of its attendant culture;

- promote an understanding of the history of the Ulster-Scots

Concerning education, the Ulster-Scots Agency offers to organise after school clubs, school drama, and both music and dance workshops29).

The Ulster-Scots Agency organises the Ulster-Scots Flagship School [USFS] programme, a cultural and educational programme to support “primary schools in the development of high quality educational and curriculum opportunities for children and young people to learn more about Ulster-Scots traditions and culture.” 30)

In 2017, the Ulster-Scots Agency launched the Ingenious Ulster Science Roadshow, which “encourages pupils to engage with science by learning about famous Ulster-Scots scientists and inventors”31). Fifty-six schools are involved in the project32). The objective behind this project is to show the role that Ulster-Scots can play in a wide range of subjects33).

The Ulster-SCots Agency recognises schools “that have developed sustainable, whole-school programmes about Ulster-Scots culture and heritage” with the Ulster-Scots School of Excellence status 34)

Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment (CCEA)

The Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment has accredited materials to learn the language as well as to learn about the community: Ulster-Scots for Primary Schools: Shared Language, Culture & Heritage.

Within the context of the Strategy 2015-2035, the CCEA was set to develop fifteen units of work for post-primary schools in 2015, which would mean a significant extension in the availability of Ulster-Scots in the curriculum. This work has been undertaken at the University of Ulster35) 36).

The Ulster-Scots Academy

The Ulster-Scots Academy is part of the Ulster-Scots Language Society and hosts a large collections of Ulster-Scots text or audio records. Its aim is to record, collect, conserve study, promote and disseminate “written and spoken Ulster-Scots in its cultural and historical contexts, in association with native speakers, and to the highest academic standards” 37)

The Ulster-Scots Community Network

The Ulster-Scots Community Network is an umbrella organisations for Ulster-Scots, “to promote awareness and understanding of the Ulster-Scots tradition in history, language and culture” 38). It has also supported the development of some primary school materials39).

Ministerial Advisory Group on the Ulster-Scots Academy (MAGUS)

Another institution that played an important role in the planning of policies in relation to Ulster-Scots is the Ministerial Advisory Group on the Ulster-Scots Academy (MAGUS), which was formed in March 2011 by the Minister for Culture, Arts and Leisure40). The MAGUS' purpose is to:

- to produce a holistic multi-year development and research strategy for the Ulster-Scots sector,

- to oversee the implementation of the strategy,

- to progress the Ulster-Scots Academy approach,

- to identify and support discrete projects under three streams of activity: language and literature; history, heritage and culture; and education and research,

- to advise the Minister on these matters41).

The term of the Board of the MAGUS ended on 31 December 2015 42).

Financial support

The Ulster-Scots Agency is funded by the Department for Communites in Northern Ireland and the Department of Arts, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs in the Republic of Ireland43).

The CCEA has received a few resources in order to develop teaching materials for primary education44).

In 2013, the Ulster University received funding from the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure on the advice of the MAGUS to create the Ulster-Scots Education project 45).

Teacher Training

Ulster-Scots is not included in primary and in-service teacher training, though at secondary teacher training, students are allowed to incorporate Ulster-Scots work 46).

Learning materials

Learning materials for Ulster-Scots in primary education have been developed by the Ulster Scots Agency in collaboration with the Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment (CCEA): Ulster-Scots for Primary School: Shared Language, Culture and Heritage. This is a program intended to revitalise the language, with the medium of instruction being English and the material available is for primary school (ages 6 to 11)47).

Education in practice

pre-school education

The Curricular Guidance for Pre-School Education states that children for whom English is an additional language and those who are being taught through the medium of Irish should be supported, but Ulster-Scots is not explicitly mentioned 48) There are a few learning materials for pre-school education, but no statistics on the use of Ulster-Scots in pre-school education are available 49).

primary school education

Ulster-Scots is not taught as a subject or used as a medium of instruction, but some schools do teach it in workshops or projects 50).

secondary school education

Ulster-Scots is not taught as a subject or used as a medium of instruction, but some schools do teach it in workshops or projects 51).

higher education

Ulster-Scots is not offered as undergraduate programme, though may be included in some projects, such as the Education project or Poetry project of the Ulster University organised in 2013 52).

The Ulster University hosts The centre for Ulster-Scots research in Irish and Scottish studies, which also aims to develop further teaching and new project at undergraduate and postgraduate level 53).

Learning resources and educational institutions

online resources

teaching materials

- Fergie an Freens - oan tha fairm Children's book for pre-school education (Eng; Fergie amnd friends on the farm)

- Primary Curriculum Resources Primary Curriculum Resources, developed by the Ulster-Scots Agency

- Ulster-Scots Education Resources Sample lessons of the accredited classroom materials (years 1-3)

- A Wheen o Wurds online basic lessons ULster-Scots, developed by the Ulster-Scots Agency

- A Wee Guide to Ulster-Scots Basic guid on Ulster-Scots, developed by the Ulster-Scots Agency

- A Bit o a Yarn series of videos developed by the Ulster -Scots agence: light-hearted conversations (‘yarns’) with native Ulster-Scots speakers

- Educational units educational units, aimed at Key stage 3 (ages 11-14), Key stage 4 (ages 14-16) and A-level (ages 16–18). Developed by the Ulster University (2013)

- Ulster-Scots Poetry Project collections of poems and some school resources, developed by the Ulster University (2013).

dictionaries and grammars

- The Hamely Tongue: A Personal Record of Ulster-Scots in County Antrim can be used as a dictionary, with more than 3000 word entries.

organisations

-

- part of the Ulster-Scots Language Society

Mercator's Regional Dossier:

Read more about Ulster Scots education in Mercator's Regional Dossier (2020).

Read more about Ulster Scots education in Mercator's Regional Dossier (2020).