Table of Contents

Lower Sorbian in Germany

Language designations:

- In the language itself: dolnoserbski

- ISO 639-3 standard: dsb

- In German, next to Niedersorbisch, the term Wendisch exists. It is often used with regard to ethnic or cultural identity rather than language, and refers to Lower Sorbs only (not Upper Sorbs).

Language vitality according to:

Click here for a full overview of the language vitality colour codes.

Linguistic aspects:

- Classification: Indo-European → Balto-Slavic → Slavic → West Slavic → Sorbian. For more information, see Lower Sorbian at Glottolog

- Script: Latin with additional diacritics. Lower Sorbian alphabet: a, b, c, č, ć, d, e, ě, f, g, h, (ch,) i, j, k, ł, l, m, n, ń, o, p, r, ŕ, s, š, ś, t, u, w, y, z, ž, ź.

Language standardization

The standardization of both Lower and Upper Sorbian is connected to Reformation. The first religious texts were translated into Sorbian in the 16th century. A Bible translation in the Cottbus/Chóśebuz dialect (1709) led to the stardardization of Lower Sorbian on its basis (Marti 1990: 23).1) Initially, the orthography of Lower Sorbian (and Upper Sorbian in Protestant areas) was based on German (Glaser 2007: 100).2) It was standardized by the scholarly organization Maćica Serbska (established in 1847, with a Lower Sorbian division, Maśica Serbska, since 1880) in the 19th-20th centuries, incorporating the Czech spelling (Marti 1990: 24).3) Language reformers of that time “took care to preserve the Slavic character of the language” but were hampered in their efforts “by hostile educational policies and the growing presence of German in the lives of most Sorbian language users. Even within the literary tradition, indigenous neologisms and Upper Sorbian loans that were supposed to replace German material ultimately failed to take root“ (Glaser 2007: 100 quoting Geskojc 1996).4)

When it comes to the spelling system, when Latin letters started being used for German after WWII (substituting the Fraktur), the change affected Lower Sorbian as well. But because education and publications in Lower Sorbian had been forbidden during the national socialist times, speakers had no time to prepare themselves for this change. What is more, the orthography reform of 1952 was based on the Upper Sorbian model, with detrimental effects on the Lower Sorbian phonetics and morphology (Norberg 2003: 89)5) and resulting in “fairly ‘artificial’ pronunciation patterns” (Glaser 2007: 101 quoting Norberg 1996).6) “In addition, a large number of German loans and internationalisms were replaced by Slavic vocabulary that was either directly borrowed from Upper Sorbian or reflected Upper Sorbian morphology” (Glaser 2007: 101).7) The reform was widely rejected by the speaker community, leading to further difficulties in sustaining Lower Sorbian social and cultural life (Norberg 2003: 90).8) It was over forty years later, in 1994, that the Lower Sorbian Language Commission's reform reversed the previous detrimental changes by separating the Lower Sorbian spelling from the Upper Sorbian system and making it correspond more closely to the Lower Sorbian pronunciation (Norberg 2003: 87).9)

The exact changes introduced by the 1994 reform are discussed in detail in Norberg 2003: 90-94.10) Glaser (2007: 101) mentions that “the strategies pursued by the reconstituted Lower Sorbian Language Commission reflect a desire to reverse the alienation of the literary form from the vernacular (Spieß 2000: 206).11) Upper Sorbian vocabulary is avoided as long as a suitable Lower Sorbian equivalent is available and likely to improve comprehension, while German material is only to be retained (or allowed to take the place of Upper Sorbian loans) if the respective item is well-established in the Lower Sorbian literary tradition”.12)

The institution responsible for the standardization of Lower Sorbian today is the Sorbian Institute (Serbski Institut).

Demographics

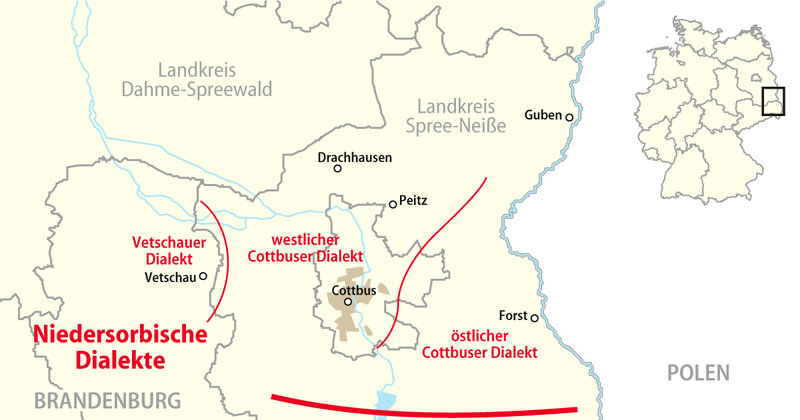

Language Area

Today's settlement area of Lower Sorbians is located within the federal state of Brandenburg, more specifically in the region of Lower Lusatia (Lausitz)-Spreewald. It covers the three administrative districts of Dahme Spreewald, Oberspreewald-Lausitz and Spree-Neisse, as well as the city of Cottbus/Chóśebuz. Out of the region's 137,317 (as of 2007) inhabitants, around 17,000 are Sorbian (Norberg 2010: 11).13)

The language continuum in Lusatia used to be divided by a line running from West to East (the barely populated forest belt) leading to the formation of two dialects (Lower Sorbian in the North and Upper Sorbian in the South) that became the foundations for the Lower Sorbian and Upper Sorbian standards. There was additionally a line running from North to South, resulting in Western and Eastern variants (Marti 1990: 22).14) Most dialects are already extinct; Lower Sorbian has/had 6 described subdialects.15)

The map below16) shows the Lower Sorbian language area.

Speaker numbers

According to the available demographic data, there were 164,000 Sorbs in Lusatia around 1840/41, 166,000 around 1880, 146,000 in 1904/05, 111.000 in 1936/38, 81,000 in 1955/56 (Lewaszkiewicz 2014: 41).17) The surveys conducted in Lusatia in the 1980s returned 67,000 Sorbian speakers and 45,000 people identifying as Sorbs.18) These numbers were, however, quickly discounted as unreliable, grossly exaggerating the number of Upper and Lower Sorbian speakers.

The studies conducted in the 1990s estimated 7,000 Lower Sorbian speakers with around 60% of them older than 60 (Lewaszkiewicz 2014: 42).19) In 2000 Elle20) estimated the number of Lower Sorbian speakers at 5,000, around the year 2010 the estimate was 2,000 (Dołowy-Rybińska 2012: 47).21) But Lewaszkiewicz (2014: 43) claims that there could have been 400 people with active knowledge of Lower Sorbian around 2000 and 200-250 after 2010.22) There are at most 10,000 speakers of both Upper and Lower Sorbian left today (Lewaszkiewicz 2014: 44).23)

Lewaszkiewicz (2014: 45) claims that by the year 2000 there was not a single person under 40 years of age who had learnt Sorbian as their native tongue at home.24) Glaser (2007: 102 quoting Elle 2003) emphasizes that in contrast to Upper Sorbian, “Lower Sorbian has no region where its survival as an everyday language is reasonably safe. Even within the official Sorbian Siedlungsgebiete (settlement areas) Sorbian speakers amount to a mere 12% (Saxony) and 7% (Brandenburg) of the total population”.25)

The table below, adapted from Glaser 2007: 103,26) shows the numbers of Sorbian speakers in Lusatia between 1849-1995, but it must be kept in mind that it refers to both Lower and Upper Sorbian:

Table 1: The number of Sorbian speakers

| Year | Total number of Sorbian speakers | Number of Lower Sorbian speakers (if known) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1849 | 140,010 | ? | Official census |

| 1858 | 164,000 | ? | Boguslawski |

| 1880 | 166,000 | 72,000 (A. Muka) | Official census |

| 1886 | 166,067 | ? | A. Muka |

| 1900 | 106,618 | ? | Official census |

| 1904 | 146,000 | ? | Čermy |

| 1905 | 157,000 | ? | Čermy |

| 1910 | 111,167 | ? | Official census |

| 1925 | 62,045 /71,029 | 22,400 | Official census (different sources) |

| 1933 | 57,167 | ? | Official census |

| 1936 | 111,000 | ? | Nowina |

| 1938 | 111,271 | ? | Nowina |

| 1945 | 143,702 | ? | Domowina |

| 1946 | 32,061 | ? | Official census |

| 1955/56 | 81,000 | 22,000 | Tschernik (1956) |

| 1987 | 67,000 | 16,200 | Sorbian Institute |

| 1995 | 58,000-65,000 | 7,000-20,000 | Jodlbauer et al. (2001) |

The table illustrates the general tendency of consistent decline over time. Differences within short periods of time (e.g. 1904/1905) or between different sources for the same year point to the unreliability of data. In most cases, the figures for Lower Sorbian are missing (in order words, Lower and Upper Sorbian speakers were counted together). The extreme difference between Domowina's estimate for 1945 and the official statistics for 1946 could be explained by the trauma caused by the Nazi regime and WWII: Sorbs preferred not to disclose their ethnicity in the official census as the memory of Nazi persecutions was still fresh. On the other hand, the figure in the 1950s could include German residents of Lusatia who refused to identify with the nation that had caused the war.

The first census after German reunification took place only in 2011 due to data protection issues and coordination difficulties between the federal states. Germany is also known for being very wary of questions concerning race and ethnicity in official statistics, making it extremely difficult to estimate the number of Lower Sorbs/Sorbian speakers at the present time.

Education of the language

History of language education:

The first schools in the Lower Sorbian settlement area were founded in the second half of the 18th century by church organizations, but were available to only a small number of Sorbian-speaking children. Since the beginning and almost exclusively, they used German as the language of instruction. With the introduction of obligatory primary education and the state taking over the responsibility for it in the 19th century, German as the language of instruction was taken for granted, but Sorbian could be taught as a subject in secondary schools. During the Weimar Republic teaching in Sorbian was at least a possibility, but it was forbidden entirely in 1938 (Marti 1990: 44-45).27)

During the GDR times, Lusatian school students of both Sorbian and German ethnic background were obliged to learn Sorbian (bilingual policy).

“In the early 1950s, a system of two types of schools with Sorbian offers was established: schools of the so-called A-type used the Sorbian language as a medium of instruction and in the B-type schools there was the possibility to learn Sorbian as a foreign language (…). In 1955, there were 11 Sorbian schools of the A-type and 94 schools of the B-type” (Mercator 2016: 13).28)

In 1962, classes in Sorbian as the language of instruction were reduced, and two years later it was decided that children would only learn Upper/Lower Sorbian if parents signed them up, which in practice meant the end of obligatory bilingual education. In one year's time, the number of students of Sorbian decreased from 12,000 to about 3,000 (Budarjowa 1991: 62).29) Thanks to the efforts of Domowina, teachers, priests and some parents the number of students of Sorbian increased again to about 6,000 in the second half of the 1970s. The interest in learning Sorbian decreased again after the German reunification. Today about 4,000 students learn Upper/Lower Sorbian at school (Lewaszkiewicz 2014: 46).30)

In 1947, an extended secondary Sorbian school (grammar school, Gymnasium) was established in Bautzen/Budyšin and in 1952 – in Cottbus/Chóśebuz (Mercator 2016: 14).31) Next to the Gymnasium in Cottbus/Chóśebuz, there is only one Sorbian primary school in Lower Lusatia (Mercator 2016: 16).32) Mercator has a very detailed list of institutions and organizations responsible for the administration and inspection of education in Brandenburg and Saxony (2016: 17-18). 33)

It is only possible to study Lower and Upper Sorbian at the University of Leipzig. In addition, some other universities offer sporadic seminars within the framework of Slavic/Slavonic studies, for example, Dresden, Saarbrücken, Potsdam and universities outside Germany (Mercator 2016: 16).34)

Legislation of language education

European legislation on minority language education

In 1997, Germany signed the European Framework Convention on National Minorities of the Council of Europe, applicable to the Danes, Frisians, Sorbians, the Sinti and Roma in Germany.

In 1999, Germany signed the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) applicable to the Danish, Frisian, Lower German, Romanes and Sorbian languages (Mercator 2016: 12).35) The ECRML recognizes the Sorbian languages separately - Upper Sorbian as a regional language in the Upper Sorbian language area in the Free State of Saxony and Lower Sorbian in the Lower Sorbian language area in the Land Brandenburg - both under Parts II and III. Part II is concerned with regional/minority language recognition as an expression of cultural wealth, the promotion and facilitation of use of such languages, their teaching, or the prohibition of unjustified exclusion or restriction, among other provisions. Part III details comprehensive rules by which the states are obliged to abide, with regard to education, administrative authorities and public services, media, cultural activities, etc. (ECRML Council of Europe website, ECRML Wikipedia page).

National legislation on minority language education

Germany recognizes four national minorities living in the country: the Danes, the Frisians, the German Sinti and Roma, and the Sorbs. Membership of a minority is considered an individual personal decision and is neither registered, reviewed nor contested by the government authorities (BMI website).

Because the current German school system is governed by the federal principles of the state (Mercator 2016: 14),36) each state is responsible for its own educational system and therefore there is no national legislation on minority language education.

Local legislation on minority language education

Lower Lusatia is located within the federal state of Brandenburg. The following laws regulate Sorbian education in Brandenburg:

Nursery schools in the Sorbian settlement area “have to teach Sorbian culture and history. The Sorbian groups get financial support from the Foundation for Sorbian People. According to the new SWG, the federal state of the Land of Brandenburg has to support the training and the further education for nursery teachers and provide Sorbian pedagogical materials” (Mercator 2016: 20-21).37)

In addition to the laws mentioned above, the Sorbian school affairs are also regulated “in other different school regulations and administrative provisions (…) schools in the Sorbian settlement area have to inform parents about the possibilities to learn Sorbian and they have to pay attention to the Sorbian/Wendish culture and history. The SWG also determined that Sorbian/Wendish representatives can participate in school conferences of bilingual schools” (Mercator 2016: 26).38)

“If there are not enough pupils for a group in one grade, it is possible to teach the pupils of two grades together. At the Lower Sorbian Grammar School all pupils have to learn Lower Sorbian” (Mercator 2016: 32).39)

Support structure for education of the language:

When it comes to education, the Sorbian/Wendish issues fall under the auspices of the Brandenburg's Ministry of of Education, Youth and Sport (das Ministerium für Bildung, Jugend und Sport). Since 2003, the Ministry has operated a special working group for Sorbian educational issues (Arbeitsgruppe sorbische/wendische Bildungsthemen). Out of that, the Lower Sorbian educational network has arisen, which comprises basically all educational institutions in Lower Lusatia. The work of this network can be assessed positively, although a permanent central coordinator is badly missed (Norberg 2010: 59-60).40)

The Witaj Language Centre (Witaj Rěcny centrum/Witaj Sprachzentrum) is responsible for coordinating the Witaj program in Lower Lusatia. It also develops teaching/learning materials, trains teachers and publishes journals and magazines that can be used in class.

Witaj program

The Witaj program was established in 1998 according to the model provided by the Breton Diwan program. Its initiator was Jan Bart, who had visited Diwan schools in Brittany and written an article about them for the Sorbian newspaper Serbske Nowiny, published in August 1992.41)

At the beginning, his idea did not raise much enthusiasm among parents. He and his associates started giving lectures about the Diwan project in kindergartens to change parents' attitudes (Elle 2006: 7).42) Another hurdle was the lack of qualified teachers. Five kindergarten teachers took part in an intensive course organized jointly by Sorbian educational institutions (die Schule für niedersorbische Sprache und Kultur, der Sorbische Schulverein and ABC) in August 1997-January 1998.

In the next 10 years, 60 more Sorbian and German kindergarten teachers took part in the intensive courses preparing to work with the Witaj program.43) At least in the first 10 years, none of the Witaj teachers were native speakers of Lower Sorbian; the Witaj kindergartens sometimes organized visits by native speakers, but these were rare and the attempts to permanently employ a native speaker consultant were unsuccessful (Elle 2006: 10).44)

The program started in Cottbus/Chóśebuz, in the kindergarten “Mato Rizo” located in the suburb of Sielow, and is now offered by 38 kindergartens in Lower and Upper Lusatia (7 of them in Lower Lusatia). Children participating in the program come overwhelmingly from German-speaking families. Participation in the program allows them to understand Sorbian and be able to formulate simple sentences before they enter primary school (Budarjowa (ed.) 2018: 9).45)

Witaj program is based on the principle of total or partial dimension. Children are spoken to in Lower Sorbian as often as possible. They learn to understand and speak it in a natural way typical for their age – through listening, singing and playing. Since the Witaj children are usually spoken to in German at home, the program can be considered a variety of the one person-one language principle and fosters early bilingualism.

In Lower Lusatia, full immersion is offered by 2 kindergartens (“Mato Rizo” in Sielow and “Villa Kunterbunt” in Cottbus/Chóśebuz) and partial immersion – in 7 kindergartens in Jänschwalde-Ost/Janšojce, Vetschau/Wětošow, Neu Zauche/Nowa Niwa, Drachhausen/Hochoza, Dissen-Striesow/Dešno-Strjažow and Burg/Bórkowy (Spreewald/Błota) (Budarjowa (ed.) 2018: 198-199).46)

Witaj started as a revitalization project in Lower Lusatia, where the state of Sorbian was (and still is) the most precarious. Over the years, however, it developed into a general early education concept for the whole Lusatia, also where Sorbian is still spoken as a family language (Upper Lusatia) (Budarjowa (ed.) 2018: 61).47)

Witaj kindergartens have a good reputation – there are usually more children whose parents are interested in signing them for the program than places available. The program is also believed to facilitate children's cognitive (e.g. easier learning, not only of languages) and social (tolerance, openness) skills. Budarjowa lists the following benefits of bi- and multi-lingual raising of children:

- bi- or multi-lingualism should be fostered as early as possible in the child's development,

- individual differences in children's language acquisition are normal and depend on many factors,

- bi- and multi-lingualism does not in principle overstrain children,

- language acquisition takes place in phases,

- bi- and multi-lingualism trains hearing (improves attention control),

- bi- and multi-lingual children are particularly creative,

- bi- and multi-lingualism facilitates logical and abstract thinking as well as concentration,

- memory loss in old age is slower in bi- and multi-linguals (Budarjowa (ed.) 2018: 62-64).48)

Fostering bi- and multi-lingualism has always been instrumentalized as an argument for participation in the Witaj program in the communication with parents and the wider community. The more scientific publications on the program often discus the advantages of bilingualism as well.49)

As the first groups of children graduated from Witaj kindergartens and transferred to primary schools, the program followed them there. In the school year 2000/2001, six children began a Witaj bilingual program at the primary school in Sielow. Out of over 1000 students learning Lower Sorbian at school, 12% participate in the Witaj bilingual education scheme. In the school year 2006/2007, in turn, the first group of Witaj children entered secondary school, and a bilingual class was established for them at the Niedersorbisches Gymnasium (Elle 2006: 12-13).50)

Table 2: Number of students participating in Witaj classes in Lower Lusatia's primary schools, adapted from Budarjowa (ed.) 2018: 20551)

| School | Grade | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Number of students | |||||||

| Briesen primary school | 8 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 53 |

| Burg primary school | 8 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 43 |

| Jänschwalde primary school | 14 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 21 | 4 | 100 |

| Sielow primary school | 15 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 10 | 9 | 77 |

| Straupitz primary school | 25 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 55 |

| Vetschau primary school | 6 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 21 |

The most significant problem with the Witaj program is the fact that none of the Witaj teachers are native speakers of Lower Sorbian. They learn the language in intensive courses and additional/further training courses (often on Saturdays). The children's language skills can only be as good at the teachers'; the Sorbian that results from this must be accepted as a legitimate Lower Sorbian language variety/practice. What is more, due to the lack of after-school activities in Lower Sorbian, the children have no opportunities to use the language outside of Witaj; the parents' involvement is low and should be increased (Norberg 2010: 87-88).52)

There have been some empirical investigations to evaluate the results of the Witaj program (e.g. Grahl 2006)53) They showed that children who had started Witaj in kindergarten achieved better results than children who had started it at school. While all children showed the ability to understand spoken Lower Sorbian, their own speaking skills were deficient. It was shown that children were only able to spend seven to ten hours per week speaking Lower Sorbian, which is not sufficient to develop speaking skills. The children's vocabulary was also tied to the subjects they were learning in Sorbian, as a result they were not able to sustain a normal conversation (Norberg 2010: 105-106).54) In some cases, 6th grade students had less competence in Lower Sorbian than kindergarten pupils.55)

At the same time, Witaj children seemed to score better in German, mathematics and English than children learning exclusively in German (Norberg 2010: 146),56) which confirms the claims of cognitive benefits of bilingual education.

Norberg 201057) is a detailed study of successes, issues, challenges and potentials of the Witaj program across different stages of education (kindergarten, primary school, secondary school).

Language learning materials:

At https://www.witaj-sprachzentrum.de/niedersorbisch/, it is possible to find the list of all the teaching/learning materials published by Domowina/Witaj:

- under “Zeitschriften” - the children's magazines Lutki and Płomje as well as the journal for Lower Sorbian language teachers Serbska šula,

- under “Download” - materials for kindergarten and school teachers of Lower Sorbian.

Education presence

preschool education

In 1998, the Sorbian School Association established the Witaj (often spelled with capitalized letters, WITAJ) program following the Breton example of Diwan immersion education in France. The concept of immersion assumes that participating children are surrounded by the target (minority) language the entire time, while they acquire the language of wider education (majority language) at home, in accordance with the principle “one person - one language”. “Based on that model, nursery schools in Lower and Upper Lusatia developed their individual Witaj-model” (Mercator 2016: 21).58)

In Lower Lusatia, few nursery schools apply the full immersion method in practice, some using the bilingual method (the teacher switches between Sorbian and German) and yet others – the supply model (children learn Sorbian customs, songs, dances, basic phrases and expressions).

Table 3: Number of schools in Lower and Upper Lusatia offering Witaj education, copied from Mercator 2016: 2259)

| region | state | church | independent | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Lusatia | 7 | 0 | 2 | 9 |

| Upper Lusatia | 8 | 3 | 19 | 30 |

| Dresden | 1 | 0 | 1 (daycare) | 2 |

Table 4: The number of children in Lower Sorbian Witaj program, copied from Mercator 2016: 2360)

| Institutions in Lower Lusatia | Number of institutions | Number of children |

|---|---|---|

| Nursery schools where children are educated in Lower Sorbian through immersion | Full immersion: 2 Partial immersion: 7 | 110 144 |

| Nursery schools with a small offer to learn Lower Sorbian | 2 | changeable |

| Total | 11 | 254+ |

primary education

In Lower Lusatia, there are almost (or) no children who are native Sorbian speakers. Therefore, since 2000, “when the first children from Lower Sorbian Witaj-nursery schools came to primary school, Sorbian institutions and primary schools developed the model of bilingual lessons (…). Witaj-education is practiced at six primary schools. At these schools pupils also have the opportunity to learn Sorbian as a foreign language. Eighteen primary schools in Lower Lusatia only offer Sorbian as a foreign language and one school offers Sorbian in extracurricular working groups” (Mercator 2016: 25).61)

“The number of bilingual lessons differs between the schools. The subjects which are taught bilingually depend on the qualifications of the teachers. The typical subjects taught bilingually are mathematics, general science, music and sports. The bilingual classes vary between 7 and 10 hours a week. It is very difficult to organise these lessons because in the same class some pupils learn Sorbian according to the Witaj education model, some pupils learn it as a foreign language and some pupils do not learn Sorbian at all” (Mercator 2016: 27).62)

All available offers to learn Lower Sorbian are optional (Mercator 2016: 28).63)

In the school year 2016/2017, 1143 students learnt Lower Sorbian as a foreign language in primary schools in Lower Lusatia (Budarjowa (ed.) 2018: 206; the publication contains detailed statistics)64), which was an increase compared to the school year 2013/2014:

Table 5: Number of primary schools with Lower Sorbian and of students learning it, copied from Mercator 2016: 2965)

| Number of schools | Number of students | |

|---|---|---|

| Lower Sorbian as a medium of instruction (Witaj program) or as a foreign language | 6 | 309 |

| Lower Sorbian as a foreign language | 17 | 1,052 |

Norberg has a full list of the 6 schools with bilingual education, 17 schools with Lower Sorbian as a foreign language, and 4 schools with Lower Sorbian working groups (2010: 71-72), as well as detailed statistics concerning the number of students in these programs (2010: 72-78).66)

secondary education

Lower Lusatia has only two secondary schools that offer Lower Sorbian classes as a foreign language on the voluntary basis. In addition, there is the Sorbian grammar school (Niedersorbisches Gymnasium) where Lower Sorbian is obligatory (Mercator 2016: 31). Students can take examinations in Lower Sorbian as a foreign language, while German is obligatory for everybody as an examination subject (Mercator 2016: 32).67)

“At grammar school, teachers use the Lower Sorbian language as the medium of instruction from the seventh to the tenth grade in some subjects, such as music, sports, ethics and history. In the ninth and tenth grade all pupils take part in these bilingual lessons, but in the seventh and eighth grade this only concerns those pupils who took part in the Witaj-education at primary school” (Mercator 2016: 33).68)

Table 6: Number of secondary schools with Lower Sorbian and of students learning it, copied from Mercator 2016: 3569)

| Number of schools | Number of students | |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary school (Burg/Bórkowy) with Lower Sorbian as a medium of instruction (Witaj) | 1 | 3 |

| Lower Sorbian Grammar school (Cottbus/Chóśebuz) as a medium of instruction (Witaj) | 1 | 186 |

| Secondary schools (Burg, Cottbus) with Lower Sorbian as a foreign language | 2 | 14 |

| Lower Sorbian Grammar school (Cottbus) with Lower Sorbian as a foreign language | 1 | 503 |

vocational education

In Germany, vocational training is meant for school-leavers who do not wish to study at university and adult learners who can do either a full-time or a part-time program (e.g., next to working). In Lower and Upper Lusatia it is possible to learn Sorbian during vocational training for kindergarten teachers. In Lower Lusatia, no kindergarten teachers or youth care workers are Lower Sorbian native speakers. All of them need to study the language during their vocational training as well as alongside their job. This makes it particularly challenging to broaden the pool of Witaj teachers (Mercator 2016: 36).70)

Table 7: Number of students learning Lower Sorbian in vocational education institutions, copied from Mercator 2016: 3971)

| Number of students per year in all classes |

|

|---|---|

| Lower Lusatia | |

| Lower Sorbian as a foreign language (voluntary offer) | 5-10 |

| Upper Lusatia | |

| Sorbian as a foreign language for all students | 200 |

| Additional intensive Upper Sorbian classes in Witaj groups | 5-15 |

higher education

The only university offering Sorbian studies in Germany is the University of Leipzig. The Institute for Sorbian Studies (Institut za sorabistiku/Institut für Sorabistik) was established in 1951. It was initially meant for Sorbian native speakers willing to work as teachers and in Sorbian institutions. Today, it incorporates German and Slavonic studies more generally, European minority studies, Sorbian literature and history, Sorbian teaching and methodology and Sorbian ethnology (Mercator 2016: 40).72) Due to the lack of lecturers for Lower Sorbian, Upper Sorbian is clearly privileged at the Institute.

Additionally, there is a group of Sorbian students at the University of Leipzig studying various subjects. It organizes lectures, discussions and festivals (Mercator 2016: 42).73) Some other German universities (e.g., Dresden, Potsdam, Tübingen, Kiel, Magdeburg and Berlin) also pay attention to the Sorbs in Lower and Upper Lusatia in their Slavic studies and linguistics as well as in historical, political, educational, geographical, cultural or other studies, but without offering regularly Sorbian language classes (Mercator 2016: 41).74)

Table 8: Number of students taking Lower Sorbian and Upper Sorbian at the University of Leipzig, copied from Mercator 2016: 4475)

| Number of students | |

|---|---|

| Lower Sorbian students | 2-6 |

| Upper Sorbian students | 30-34 |

| Total | 32-40 |

The Brandenburg University of Technology (die Brandenburgische Technische Universität, BTU) in Cottbus signed a cooperation agreement with the Domowina in 2008, to organize common projects for the preservation of Sorbian/Wendish language, identity and culture (Norberg 2010: 13).76)

adult education

Adult education centres (Volkshochschule) have a long tradition in Germany, offering courses for professional qualifications and a variety of personal interests at a relatively small fee. In Lower Lusatia, Lower Sorbian language classes are provided by various institutions, including the Witaj Language Centre and the Šula za dolnoserbsku rěc a kulturu/Schule für niedersorbische Sprache und Kultur/School for Lower Sorbian Language and Culture. This school “organises many one-day projects with communication and cultural activities where participants can use and practise their Lower Sorbian language skills. The school organised 29 of such activities for 546 participants in 2014” (Mercator 2016: 45-47).77)

Table 9: Number of courses organized by the School for Lower Sorbian Language and Culture and number of participants per year, copied from Mercator 2016: 4678)

| Number of courses/year | Number of participants/year | |

|---|---|---|

| School for Lower Sorbian Language and Culture | 35-50 | 250-300 |

Online learning resources

- Dolnoserbski: dictionaries, corpora and other resources]]

- Sotra: automatic translator between Upper Sorbian, Lower Sorbian and German

- Sorbisch Lernen: Lower Sorbian online course for levels A1 and A2 (also in English)]]

- Sorbische Wendische Sprachschule: website of the Lower Sorbian School of Language and Culture]]

Mercator's Regional Dossier:

Read more about Lower Sorbian language education in Mercator's Regional Dossier (2016).

Read more about Lower Sorbian language education in Mercator's Regional Dossier (2016).