Table of Contents

Griko in Italy

Language designations:

- In the language itself: Griko or Katoitaliotika

- ISO 639-3 standard: ISO 639-3-ell*

*Modern Greek and Griko use the same code as Griko is derived from Greek

Language vitality according to:

Click here for a full overview of the language vitality colour codes.

Linguistic aspects:

- Script: Latin or Greek 2

1: There are two theories as what the origins of Griko are. The Magna Grecia theory is supported by Greek linguists stating that Griko is derived from Doric Greek while the Byzantine Theory is supported by Italian linguists stating that Griko is derived from the Ionic-Attic variety of Greek. 1)

2: Italian and Greek linguists use the Latin script while some older Greek linguists from the nineteen-nineties use the Greek script.

Language standardization

There is no universal standardised orthography in use as Griko is a typical oral language which tends to vary from village to village maintaining mutual intelligibility between the speakers. Griko can be written with two different scripts, with Italian linguists using the Latin script and some Greek linguists using the Greek script.

There have been various works published on the Griko language. This includes grammar books such as ‘The grammar book of the Greek varieties of Southern Italy’ written by Karanastasis (1997)2), lexicons such as ‘The historical lexicon of the Greek varieties of Southern Italy', which is a five volume lexicon by Karanastasis (1984)3), PhD theses and journal articles by Italian and Greek linguists, such as the article 'The Griko Dialect of Salento: Balkan Features and Linguistic Contact' by Valeria Baldissera (2013). 4)

Demographics

Language Area

Griko is spoken in the region of Salento, province of Lecce in the administrative area of Apulia, which is also known as Grecia Salentina. A cultural union called 'The Union of the Towns of Grecìa Salentina (Unione dei Comuni della Grecìa Salentina' was founded in 1966 with the aim to promote the language and culture by organising research in universities, by teaching the language in schools and by publishing books and poetry in Griko.5)

Grecia Salentina is made up by nine villages, covering an area of around 143,90 km². These villages are Calimera, Castrignano dei Greci, Corigliano d’Otranto, Martano, Martignano, Melpignano, Soleto, Sternatia, and Zollino. However, the use of Griko has ceased in Melpignano and Soleto as it is primarily spoken by the elderly.6)

Italiot-Greek varieties

Griko should not be confused with Greko, also known as Grekanico, despite both being Italiot-Greek languages.Griko and Greko are mutually intelligible due to both languages being derived from Greek however, the primary difference between these two languages is that Griko is spoken in Salento while Greko is spoken in Calabria. Furthermore, they have some differences regarding their grammar and the languages they have come into contact with throughout history. Griko has been in language contact with Italian and Salentino while Greko has been in language contact with Calabrian and Italian. Despite both Griko and Greko being derived from Greek, they both developed independently. 7)

The image shows the speaker communities of Griko in Salento and Greko in Calabria8).

Speaker numbers

The total population of Grecia Salentina in 2015 was estimated to be around 41,500 people, with the language being spoken by around 20,500 speakers, mostly elderly people. The reason why Griko is mostly spoken by the elderly is due to migration outside of Griko speaker areas by the younger generation and due to preference of teaching Italian for socioeconomic advantages. 9) 10)

Linguistic repertoire

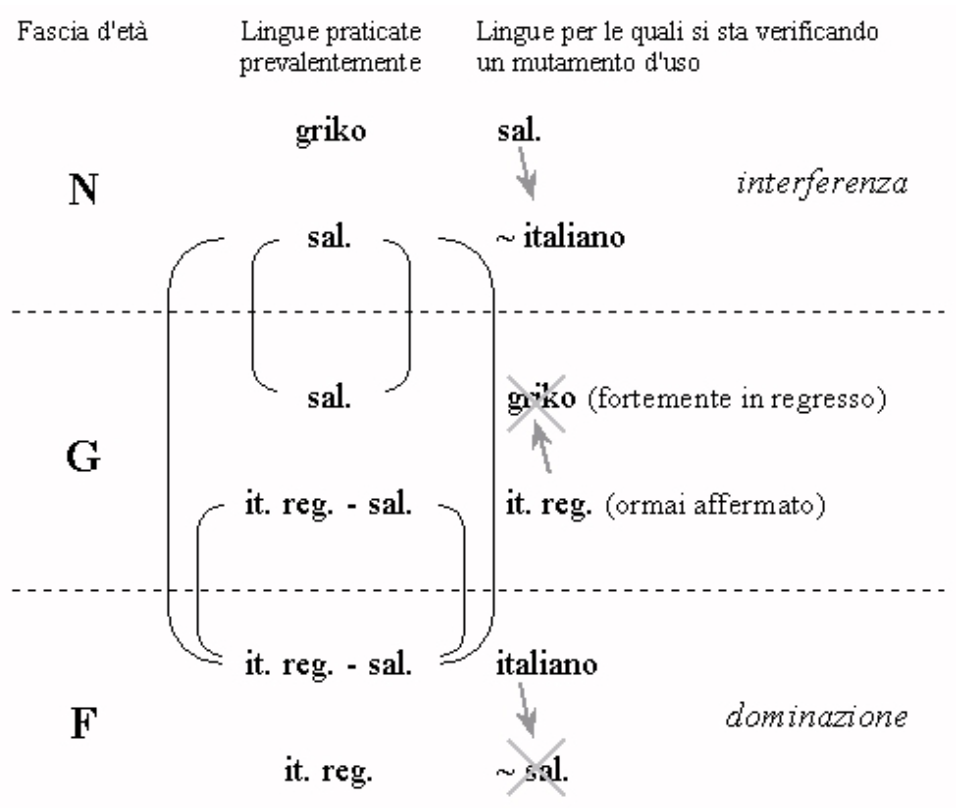

The image below describes the linguistic repertoire in Salento, which was taken from the 2015 journal article titled Griko and Modern Greek in Grecia Salentina: an overview written by Angeliki Douri and Dario De Santis.The region where Griko is spoken, Salento, is known for its linguistic diversity as the speakers do not only speak Griko, but also Salentino (a Romance variety) and Italian. The grandparents/elderly (N) speak Griko amongst themselves while they use Salentino as well as Italian, with incomplete knowledge, with the parents (G) and the children (F). Parents (G) use Salentino to communicate with the grandparents/elderly (N) as the parents have incomplete or passive knowledge of Griko, which they rarely or almost never use, while with the children (F), they use either Italian or Salentino. As the children (F) do not speak or understand Griko, they use Italian or Salentino with the parents (G) and Salentino with the grandparents/elderly (N). However, the scheme represents the linguistic repertoire in Salento, it does tend to vary from speaker to speaker and family to family. 11)

The image shows the linguistic repertoire in Salento of the grandparents/elderly (N), the parents (G), and the children (F) 12).

Prestige of Griko

Griko in the past was regarded as a language of little or no value due to people preferring the use of Italian. Griko was regarded as the low (L) language while Italian was regarded as the high (H) language, as Italian was used in more domains such as in school as a medium of instruction. 13) 14)

Education of Griko

History of Griko education:

According to the 2016 journal article, Performing Griko beyond death written by Manuela Pellegrino. Education in Italy became compulsory in 1924 but up until 1930, Griko was the mother tongue for the majority of the speakers in Grecia Salentina. In the 1950s and 1960s, students had to learn Italian, the national language, in school. However in Grecia Salentina, the spoken language was Griko. Between the 1960s and 1970s, many students abandoned the use of Griko as they prioritized Italian as it would benefit them socioeconomically compared to Griko. Interestingly, after the 1970s, due to a decrease in the number of Griko speakers and due to the belief that the Griko were losing their culture, there was an active interest to bring the language back. 15)

Legislation of language education

European Legislation

European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

Italy has signed the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in 2000, but has not ratified it.16)

Framework Convention on the Protection of National Minorities

Italy has signed and ratified the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

As a result, different projects have taken place which have aimed for the protection of Griko such as17):

- The financing of the “Griko Project” by the Ministry of Education which introduced Griko as a subject in kindergarten, primary school and junior secondary school in the Municipalities of Grecia Salentina.

- Broadcasting of radio programs in Griko.

- Distribution of periodicals in Griko.

- Publishing of poems and texts in Griko in the local press when celebrating a patrons Saints Day.

National Legislation

Under the Italian legislation of the Law n.482/99 of 1999, article 2, the Italian parliament recognises the Griko community as a Greek ethnic and linguistic minority, with the state protecting the language and the culture, alongside 11 other languages (Albanian, Catalan, German,Slovenian, Croatian, French, Franco-Provencal, Friulian, Ladin, Occitan, Sardinian).18)

Support structure for education of the language:

Despite Griko being a language that is in decline, there have been many efforts to come up with teaching material by both speakers, teachers and members of the community to revitalize the language. In 2011, the European Program ‘Pos Màtome Griko’19) 20) (How we learn Griko) was created whose aim was the teaching of the Griko language and culture. The curriculum is aimed for both adults and children who want to learn Griko as beginners or for those who want to increase their competence. The teaching material follow the CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference for Language) levels, ranging from A1 to B2. The A1 and A2 levels are primarily aimed for children and the B1 and B2 levels for adults.

The materials focus on grammar, phonetics, vocabulary and sociolinguistic information. The program has also created a Griko-Italian-Greek dictionary to help the students.

The aim of this project is to:

- Promote and enhance Griko

- Promote the Griko culture and language via workshops and seminars

- Improve the educational resources of institutions interested in the teaching of Griko

- Creation of an e-learning platform for free access to educational material and information on programs and courses

Τhe program is targeted to:

- Students and teachers of schools in Griko speaking areas

- Adults living in Grecia Salentina

- Grecia Salentina Municipalities

- Universities with a department in Modern Greek language and culture

- Hellenic Communities and Hellenic Cultural Centres in Italy

The program was created via various institutions and organisations such as:

- Agenzia per il patrimonio culturale euromediterraneo in Italy

- Greek-British college “Megas Alexandros” in Greece

- Publisher ALFA in Greece

- The University of Cyprus – Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek studies in Cyprus

- The Istituto Culture Mediterranee in Italy

Education Presence

Griko

Griko is a compulsory subject in school from nursery up to secondary school in Salento. However, there is no unified agreement about the teaching method of the language as every school acts on its own. The headmaster of the school takes the decisions on the distribution of resources, and in which grades and which ways Griko is taught. Normally, Griko is taught for 1 hour per week, consisting of Griko poetry, folklore, dances and traditions. During those classes, not much emphasis is given on the grammar and the actual usage of the language. This is due to the external Griko experts who teach the subject, but who learnt Griko while growing up, but not as their first language. Due to lack of economic resources and due to lack of available teaching hours, there has been a decline in teaching. 21)

Modern Greek

Modern Greek in Grecia Salentina was also taught, dating back to the 1970s, when some schools offered comparative courses of Griko and Modern Greek. However, it was only after 1994 that the teaching of Modern Greek in Grecia Salentina became official and systematic. Since then, the Greek Ministry of Education has been sending native Modern Greek teachers to the schools to teach Greek. Modern Greek is taught as a foreign language to people who are not of Greek origin and to those who have not had any contact with Greek.22)

The comparative teaching of Modern Greek and Griko has been noted to have pros and cons. An advantage of teaching Modern Greek and Griko is that it can fill lexical gaps in Griko by using Modern Greek vocabulary instead of Italian. However, there are also disadvantages. For example, there is not enough time available to teach both languages in an hour, as half an hour is dedicated to each language. A second issue with teaching Modern Greek alongside Griko is that there is a lack of bilingual teachers in both languages. A third issue is that, as students are not competent in both languages, they cannot take advantage of knowing one language to learn another or they may show preference in learning one language over another due to the prestige of that language. A last problem regarding teaching Modern Greek and Griko together is that both languages are written using different script, Modern Greek is written using the Greek script while Griko is written using the Latin script. Students therefor need to learn both scripts which can cause confusion.23)

Online learning resources

- Glossa Grika - provides texts examples, voice recordings and grammar points

- Greco Sud Italia - an Italian translation of the in-depth grammar book 'The Greek varieties of Southern Italy' by Karanastasis (1997)

- Rize Grike - provides an overview on Griko grammar

- Griko video example - a video interview of a Griko speaker

- Griko script - Griko alphabet in Latin and Greek script

- 'Pos Màtome Griko' brochure - 'Pos Màtome Griko' brochure