Table of Contents

Karaim in Lithuania and Ukraine

<colorgreen> updates welcome. </color>

Language designations:

- In the language itself:

- Crimean dialect: къарай тили,

- Trakai dialect: karaj tili

- traditional Hebrew name: lashon kedar לשון קדר

- Turkish dialect: karay dili

- ISO 639-3 standard: kdr

Language vitality according to:

Click here for a full overview of the language vitality colour codes.

Linguistic aspects:

- Script: Cyrillic in Ukraine and Latin in Lithuania

Language standardization

Throughout history, it was important for Karaim speakers to understand written text for ritualistic purposes, however these texts were dependent on the group's locality and so Cyrillic, Latin and Hebrew have all been used in the past 1) Today there is no standardized written language and comprehensive documentation into this variety is still very much needed. However, a previous Lithuanian Karaim leader (1924-2000), called an 'Ullu Hazzam', published a grammar textbook for children, but due to the Lithuanian orthography used, these resources are not so accessible to non Lithuanian Karaims 2). There have also been instances of external bodies documenting the language 3).

The three major dialects with which the language functioned are/were:

- Crimean (Eastern dialect): Although the suspected origins of modern Karaims, since the early 1900s this dialect has been considered extinct 4).

- Łuck-Halicz / Lutsk-Halych (Western Ukraine): After World War I, there was a cultural renaissance and many works of fiction, a grammar and a dictionary were published in Lutsk 5). After World War II however, all dialects suffered from the Russification of their territories, which led to geographical dispersion and significant language contact with majority varieties. Despite a period of linguistic prosperity, the Łuck-Halicz / Lutsk-Halych dialect has now extremely few numbers left, with some sources quoting as little as two fluent speakers 6).

Across the dialects differences occur mainly in vocabulary, phonetics and orthography. As Csató and Nathan (2007) 10) state:

“The divergence of the Karaim communities’ literary traditions has thus resulted in a very complex situation. Lithuanian Karaims write in the Lithuanian system, the Karaims of Poland and Halich in the Polish one, other Karaim communities of Ukraine and Russia write in Russian, and Karaims of the diaspora beyond these countries have difficulty in reading any of them. There is no move to introduce Hebrew literacy in any of the communities, partly due to the strong emphasis that most Karaims place on their Turkic ethnic identity.”

In other words, standardization across the Karaim language has been problematic to say the least.

One of the few documented cases of Karaim can be heard here:

Demographics

Language Area

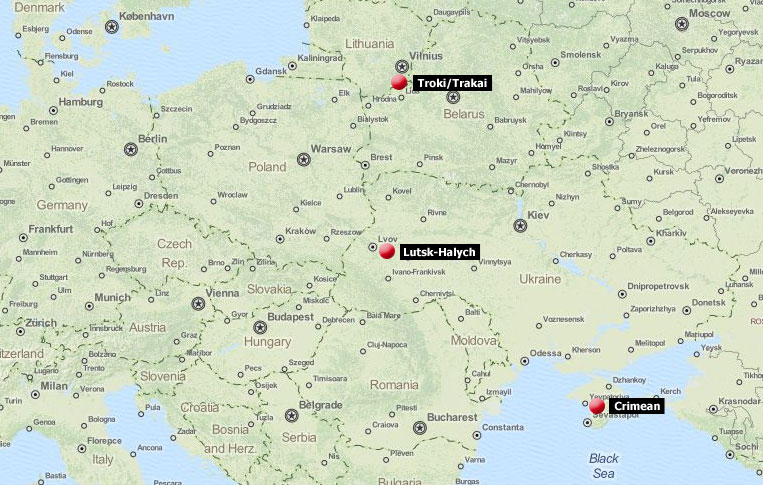

The Karaims are most predominantly found in Lithuania, Western Ukraine and the Crimea, while a small percentage can also be found in Poland, Romania and the USA11). Historically, they originate from the mountainous center of the Crimea, but many were resettled by Lithuanians between the 12th and 16th centuries, which led to their current presence around Vilnius today 12). Beyond these three major regions, the Karaims are also residing in several Russian cities and in the Caucasus 13).

Map of Karaim dialects 14)

Speaker numbers

As noted above, the number of Karaim speakers existing today is uncertain. However it can be assumed to be dwindling. Those who do hold a higher proficiency are predominantly elderly, while younger generations experience high amounts of interference from other majority languages in their vicinity, such as Russian and other Baltic varieties 15).

According to Karaim at Languages in Danger's Book of Knowledge, there are some 120 speakers left in Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine. Of this population, in Lithuania and Poland, it is believed that 86 can speak and understand Kariam, whereas 39 are able to speak, understand, read and write.

Conversely, the Ethnologue states that there are 84 speakers left in all countries.

Education of the language

History of language education:

As the Karaim language is not standardized it is very difficult to institutionalize within the framework of education. Despite having once a real chance at linguistic prosperity, with speakers in Lithuania reaching an estimated 5000 people in the late 12th century, the language has since depleted century after century 16).

It is believed that in pre-war Poland efforts were made to organize some form of language education, as the Karaim faith (similar to Judaism), required believers to understand the religious texts written in Karaim 17). Children would learn to write and read Karaim, through the Hebrew script, at religious schools (a midrash). However these differed dialectically from community to community 18). Once the Soviet Union took over however, any thoughts of a standardized Karaim education were abandoned, along with their faith and farms 19).

Today there is a big push for revitalization both within the community and from third parties, such as from Uppsala University in Sweden, where they offer a unique course in Karaim, covering both linguistic and cultural knowledge. 20). Beyond this there is a regular Karaim language Summer school and sporadic language learning events provided by the Karaim community.

Legislation of language education

Lithuania

Lithuania's constitution considering minorities is quite accepting, as Article 37 of the Constitution spells out that, “citizens who belong to ethnic communities shall have the right to foster their language, culture and customs” and that according to Article 45, “national minorities in Lithuania have the right to education in their own language.” The state however will only finance minority language schools if the school is located in a, “populous and compact community of the ethnic minority.” Although Karaim are a recognized minority within Lithuania, their meager numbers are insufficient for traditional schooling in their language.

In 2000, Lithuania ratified the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities of the Council of Europe, recognising the Karaite minority alongside the Russian, Polish, Jewish, Belarussian, Tartar, Roma, German and Ukrainian minorities 21).

To this date, Lithuania has not ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages and so Karaim does not reap any benefit from this treaty 22).

Poland

Poland has ratified the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities of the Council of Europe, recognizing the Karaim minority as a religious minority: “Karaites have lost their knowledge of their mother tongue; it is Karaite religion, originating from Judaism and Islam which distinguishes them” 23).

Poland has also recognized the Karaim minority in the European Charter for Regnional and Minority Languages under part II and III. You can read the latest report (2019) here

At a national level, Poland has recognized the Karaims as an ethnic minority which permits them the right under Article 35 of their constitution:

- The Republic of Poland shall ensure Polish citizens belonging to national or ethnic minorities the freedom to maintain and develop their own language, to maintain customs and traditions, and to develop their own culture.

- National and ethnic minorities shall have the right to establish educational and cultural institutions, institutions designed to protect religious identity, as well as to participate in the resolution of matters connected with their cultural identity.

Similarly to that in Lithuania, despite this legislature, the small population of Karaim speakers allows for little governmental attention or support in establishing more concrete public schooling or education.

Ukraine

In the Ukraine, Karaim is recognised in the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages under part II, though Karaim speakers are believed to be few or extinct 24).

In the Ukraine, a law on education passed in September 5, 2017, withdrawing the right to education in a minority language. For primary schools seperate groups can still be taught in the minority languages and in secondary schools minority languages can be taught as a subject if it is a EU language. SOme exceptions are made for ““indigenous languages”, which seem to be non-kinstate languages such as Karaim 25) 26). The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) has been concerned about this law in light of the Framework Convention, and states that the law is “a major impediment to the teaching of national minorities' mother tongues” 27).

Support structure for education of the language:

Lithuania

In Lithuania, the Department for National Minorities and Emigrants is responsible for ensuring government language policy is upheld. This institution also mediates between sultural/educational minority associations and governmental organizations and support 28).

Education in practice

Currently there is no formal Karaim language education in any of the countries where Karaims reside. The only known source of language schooling is the annual Summer School held in Trakai, Lithuania. These Summer schools are provided by Éva Csató, a Hungarian linguist whose research explores Turkic languages, and uses a unique multimedia method for teaching 29). It is hoped that with the cooperation of a proficient Karaim speaking community member and external organisations, such as Mercator, teaching could be continued more frequently 30)

Beyond that, the university of Uppsala, in Sweden, has a Karaim course on offer.

Learning resources and educational institutions

- Endangered Languages resources

- Learn Karaim Language with word lists

- Karaim Official Website in Lithuania (not in English)

- Karaimi (not in English)