Table of Contents

Greek in Ukraine

Language designations:

- In the language itself: Mariupol Greek or Rumeika or Azov Greek (in English) or Румейська мова (in Ukranian) or Ρωμαίικα (in Greek)

- ISO 639-3 standard: Mariupol Greek's ISO 639-3-ell*

*Mariupol Greek does not have its own ISO code as it is derived from Greek

Language vitality according to:

| UNESCO | Ethnologue | Endangered Languages | Glottolog |

|---|---|---|---|

| n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

No database has information available for Greek in Ukraine specifically.

Click here for a full overview of the language vitality colour codes.

Linguistic aspects:

- Classification: Indo-European → Hellenic → Attic-Ionic → Pontic* → Mariupol Greek or Rumeika. For more information, see Mariupolitan Greek at mari1411

- Script: Greek or Cyrillic

*Amongst Greek scholars there is a debate whether Mariupol Greek is derived from Pontic Greek or Northern Greek dialects as Mariupol Greek presents similarities with both Pontic and Northern Greek dialects

Language standardization

Rumeika can be written both with the Cyrillic script, which was developed by Andrei Biletski in 1969 based on the Ukranian and Russian alphabet, and the Greek script however for the Greek script, a reformed Greek orthography with 30 letters is used. For the teaching of Modern Greek, the Modern Greek script is used which is regulated by the Center for the Greek Language (Κέντρον Ελληνικής Γλώσσας). 1)

Demographics

Language Area

Mariupol Greek or Rumeika is spoken in the regions of Crimea (northern coast of the black sea), Zaporizhia (south Ukraine) and Odessa (southwestern Ukraine) however, the majority of Hellenic minority live at Donetsk (eastern Ukraine) by the ethnic Greeks who live in Mariupol and surrounding villages. Modern Greek is also commonly spoken amongst the inhabitants.2)

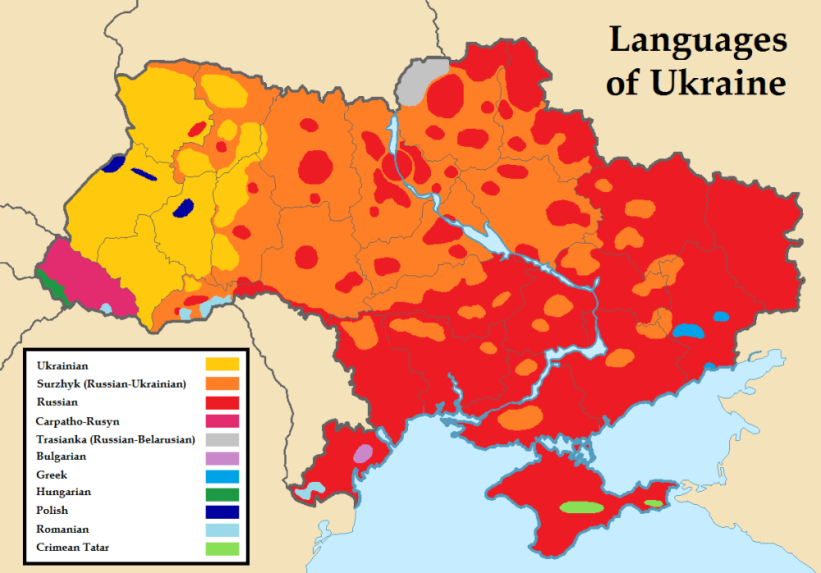

The map shows the various languages spoken in Ukraine, with the colour blue denoting the region (Donetsk) where Greek (either Modern Greek or Rumeika) is spoken.

Speaker numbers

In a 2001 Ukrainian Consensus, it was estimated that the population of Ukrainians of Greek origins was around 91,500, found in different regions in the country (table below). The reason why there are so many Ukrainians of Greek origin is due to migration from Crimea, dating back to the 18th century due to intermarriage between Greeks and Ukrainians. 4)5)6)7)8)9)

| Region | Population |

|---|---|

| Donetsk | 77,500 |

| Crimea | 2,800 |

| Zaporizhzhia | 2,200 |

| Odessa | 2,100 |

| Dnipropetrovs'k | 1.100 |

| Rest of Ukraine | 5,800 |

| Total population | 91.500 |

The table indicates the population of Greeks in Ukraine based on region according to the 2001 Ukrainian Census.

Sociolinguistics

The variety of Greek spoken in Ukraine is known as Rumeika and it is believed to be derived from Ῥωμαῖος ‘citizen of the Byzantine empire’. According to a study by Prof. I. Sokolov, D. Spiridonov and Prof. M. Sergievskij in 1927–1934, the study found that Rumeika consisted of 5 sub dialects, which mostly differed in phonetics and some morphological and lexical features. 10)

Despite the various subdialects of Rumeika, there still is a high degree of mutual intelligibility between them. Rumeika differs from Modern Greek, from a syntactic and morphological perspective, Rumeika is much more similar to Pontic Greek and some of the dialects of Northern Greece but lexically, the language is influenced by Turkish and Russian to the extent that it is not mutually intelligible by Modern Greek speakers. 11).

Amongst the areas where Greeks inhabit, there has been a steady decrease in the number of speakers of Rumeika as the people opt to learn Modern Greek. Rumeika is used by the older generation while Modern Greek is used by the younger one. Within the Greek Ukrainian population in Ukraine, around 6,4% (around 5000 people) claim to have Greek (Rumeika) as their mother tongue while the rest claim to have have Russian (88,5%) or Ukrainian (4.5%). The first reason reason why Russian has a high number of speakers in Ukraine, despite Ukranian being the official language of Ukraine, is due to the official language of the USSR, that Ukraine was part of, being Russian. The second reason why Russian has a high number of speakers in Ukraine is due to Russian being used as a lingua franca between different ethnic minorities. All academic institutions of the time taught in Russian rather than Ukranian.12)

Education of the language

History of language education:

The teaching of the Greek language in Ukraine has a long history, which dates back to the 16th and 17th century, with the language being taught in fraternal schools in universities such as the Lviv fraternal school Arseniy Ellasonskiy whose pupils wrote grammars of the Greek language or the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, which dates back to 1632, which incorporated a 12 year Greek language teaching program. In the 18th century, the teaching of the Greek language was expanded to colleges in numerous cities such as Odessa, Poltava, Kharkiv, Kherson and Chernivtsithe. In the 19th century, universities in Odessa, Kharkiv and Lviv provided programs which focused on the study of Ancient Greek, history, philosophy and culture. Kyiv University of Saint Volodymy and Lviv University were the most pioneering universities at the time regarding as Kyiv University from the day of its foundation in 1834 had the chair of the Greek language and Lviv University was one of the mightiest centres of the Greek language. 13)

Prior to 1937, Soviet language policy was focused on promoting minority language use in education, publishing and local administration by creating alphabets for languages that did not have a standardized script. This policy in Mariupol, the biggest region inhabited by Greeks, took place in the villages from 1926 by focusing on primary education in Modern Greek. In the absence of such books, teachers and students would use the local Greek newspaper called “Kollectivists” and the children magazine called “Pioneros”, however, both newspapers were written in a combination of Rumeika and Modern Greek while the children’s magazine was written in Modern Greek. However, due to Rumeika’s low prestige, Modern Greek was chosen to be taught at Rumeik schools. 14)

The Greek language continued to be taught throughout the centuries but in 1937, the teaching came to a standstill as Joseph Stalin banned the Greek-language instruction in local schools. Between the years 1930 till 1980, only the Ukrainian language was allowed to be taught and spoken in schools, with the minority languages being banned in education and only allowed to be used at home. This had a consequence for the Greek speaking population of Ukraine to lose Rumeika. 15)

After the fall of the Soviet Union around 1990, there was a resurgence in learning Greek. Amongst the villages in Mariupol, there was a discussion whether to keep teaching Rumeika or Modern Greek as a language. The population decided that they should focus on learning Modern Greek as it would benefit them for communication if they ever visited Greece. 16)

Due to the lack of Greek teachers to teach the language in the region, a conference took place in 1990 whereby a professor from the University of Ioannina, Vasileios Kirkos with a team visited the region in order to hear the demands of the people. When the professor returned to Greece, 5 of the residence of Mariupol where invited for 8 months at the University of Ioannina to learn Greek. After the return of the residence, the University of Mariupol implemented Greek as a mandatory subject in its philological classes and in 1996, the board of Greek education was created. 17)

Legislation of language education

European legislation on minority language education

European Charter of Regional and Minority languages

Ukraine signed the European Charter of Regional and Minority languages on the 2nd of May 1996 but ratified it on the 19th of September 2005, with the legislation being put into force on the 1st of January 2006. Under the charter, Ukraine has declared it will protect all the minority languages throughout Ukraine. 18)

Framework Convention on the Protection of National Minorities

Ukraine signed the Framework Convention on the Protection of National Minorities in September 1997 and ratified it in December 1997 however, the framework convention came into force during May 1998. Under the Framework convention different projects have taken place which help the maintenance of Greek in Ukraine such as:

Television and radio Broadcasting:

- The TV and radio organisation “Mariupol TV” broadcasts the TV program “Az yes'm” in Greek twice a week for 20 minutes.

- The TV and radio company “Crimea” broadcast radio programs such “Kalimera” and “Yals” for 15 minutes per month and the broadcasting of “Eleftheria” 4 times a week for 15 minutes.

- The creation of Greek societies. 19)

National legislation on minority language education

According to the constitution of Ukraine of 1996, under article 10, the state guarantees constitutional protection for other minority languages spoken in Ukraine however, the 2017 Education Law has made Ukrainian the required language of study in states school with the instruction in other languages as a separate subject. 20)21)

Support structure for education of the language:

Language learning materials:

Unfortunately, not many materials in Rumeika exist as many people prefer to learn Modern Greek. As for teaching material, the Greek language teachers tend to use the same books used in Modern Greece in Greek schools. 22)

Education presence

Primary and Secondary Education

According to the Federation of the Greek Societies in Ukraine, since 2018, there have been over 4000 students who learn Greek as a mandatory second language taught in 58 institutional centres including primary and secondary schools and Sunday schools. 23) The Greek language is taught from the 5th grade till the 12th grade however, as of 2018, students from the 1st grade will learn Greek as a second language. Interestingly, not only students of Greek origin learn Greek, but students also from different backgrounds with an interest in Greek language and culture learn the language. 24)

Tertiary Education

Some universities in Ukraine provide degrees or language courses on Modern Greek such as:

- L'viv State University Centre of Greek Language and Culture

- Mariupol State University of Humanities College of Greek Philology

- National University I.I.M. Mechnikovo Faculty of Foreign Languages, Chair for Translation and Interpretation, Center of Modern Greek Studies

- Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv The National Institute of Philology

- Tauric National University "V. I. Vernadsky" Faculty of Foreign Philology, Deparrtment of Greek Philology

Online learning resources

Organizations

- Federation of Greek Societies in Ukraine unites 100 Greek communities from 19 regions of Ukraine 26)